'Grizzly Man' and the Harsh Indifference of Nature

I have been away for a couple weeks, continuing the adjustment into office life and trucking along with my freelance work at Collider, so I have not found much time to sit and write here. But I saw a documentary, Grizzly Man (Werner Herzog), a couple of weeks ago that profoundly affected me, so I wanted to share the story of Timothy Treadwell.

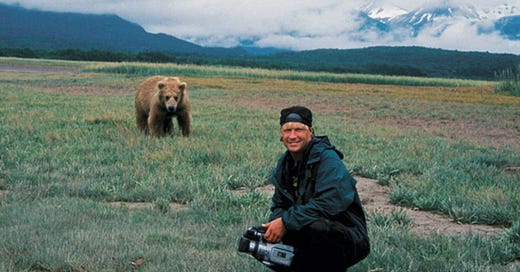

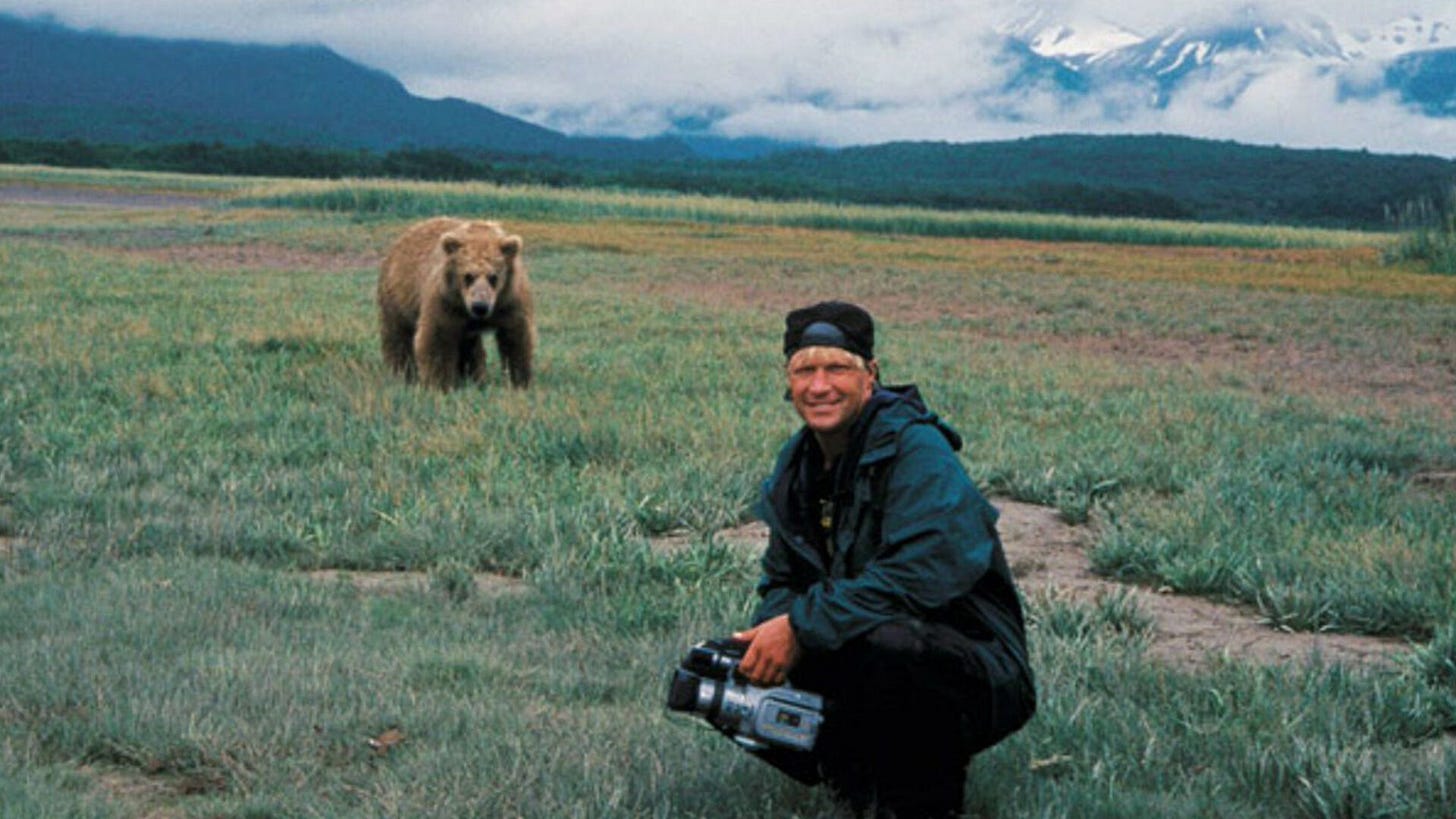

Timothy Treadwell was an American environmentalist and advocate for the protection and sanctuary of brown bears in their natural habitat. Armed with no weapons, only a camera to document his experience, Treadwell would make extended stays in the Alaskan coastal regions, living among these bears, with whom he developed what felt like sincerely meaningful relationships. Herzog’s documentary is constructed with Treadwell’s extensive self-recorded footage and photography, as well as interviews with friends and family. Treadwell was dedicated to his cause, and quite eccentric. A mystifying figure who you cannot help but to love a little bit as you see how passionately he approached the issue of nature conservation.

But his stay among the bears eventually went awry, and in October of 2003, he and his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard, were killed by a bear in a brutal attack, one which was recorded on Treadwell’s audio equipment. Herzog thankfully spares us the sounds of their final moments, but I found a lot to learn not only in Treadwell and Huguenard’s deaths, but also the general way that Treadwell lived his extraordinary life before their fatal end.

Treadwell comes off as a strange figure, sort of a nature documentary’s answer to Tommy Wiseau, the bizarre and mysterious figure behind the cult-film The Room. I say this because both are people who seem desperate to escape something, and the avenues they found for doing that are these unusual creative or lifestyle pursuits that they pour absolutely every single resource and minute of their lives into. In Wiseau’s case, it resulted in an unintentionally hilarious exercise in bad filmmaking, but in Treadwell’s, the result was quite bleak.

There is something admirable about the level of dedication it takes to do what people like Treadwell or Wiseau do, to boldly stake your claim in a place where you are far from an authority, and to will yourself into a legendary status. But it also serves as a sobering reflection of how unresolved problems, some of which in Treadwell’s case most likely stem from mental health issues, can cause people to break from reality and behave in reckless or unconventional ways. It is hard to know when the line is crossed between harmless eccentricity and dangerous, self-destructive delusions, but it is clear that Treadwell crossed that line.

What is frustrating about Treadwell’s efforts, a point which reflects the lack of self-awareness in his approach, is that his ultimate goal of becoming one with the harmonious natural world not only gets him brutally killed, but also his partner, and on top of that, his demise leading to two bears being killed during the recovery of his body makes his entire pursuit as the protector of the bears a cruel, ironic twist of fate.

Treadwell thought he could return to some pre-civilization status of concord with nature. His fatal mistake is that his understanding of how we fit in the natural world was always naive. We cannot go back to what never existed in the first place, people were always too smart and too self-preserving to make that work, and wild animals are ultimately not going to mourn what they can only conceptualize as sustinance. Amidst the carnage of blood and bone, Timothy’s belief in the harmony of nature is also torn to shreds, there is no order in this place, just cold indifference and hunger.